How to reach consensus in the different Egyptian points of view?

During the long days of waiting for the car and the customs hassle, we had the opportunity to speak to a few Egyptians from Alexandria and Cairo. We were eager to meet some locals, to learn about their views on the situation. We had many questions, like how the messages in the news are regarded, how people see the Muslim Brotherhood party and Morsi, how the role of the army is perceived and how they see their own role in the conflict.

From the news, newspapers and talking to people, there are roughly four angles to be distinguished. Off course what we write here is a personal reflection of what we saw and learned during our short time here and is not a full account of the situation here.

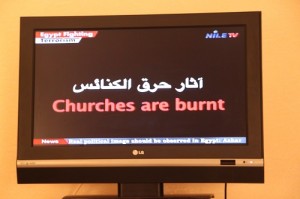

One group consists of people against Morsi. Their main arguments are that he didn’t deliver what he promised in 2011 and he introduced laws that gave disproportional power to the MB party. They also believe that the army is supporting the people in bringing and keeping peace in the country. It seems that people might have ‘forgotten’ about the role that the army played in escalating the situation and using violence on a large scale. Or they justify it by saying it is in the benefit of the people. The message that the MB are terrorists and ‘may turn into radical Muslims or jihad warriors’, resonates with them.

We met Ahmed, an Egyptian born and raised here, now owner of a restaurant in Philadelphia. Ahmed is mainly against MB and against violence. When we asked him why he was in Egypt, he replied ‘well, to demonstrate, off course. To support the people in the revolution’. Ahmed seemed to be broad minded, as he told us that he had many friends that were MB. ‘But’, he added, ‘the MB party has the potential to turn into fanatics or terrorists that will force us to live more conservatively and hinder economic growth. We should stop that.’ So what Ahmed describes is not the condemnation of the acts done by the MB today, but what they might become in the future.

That’s a parallel that we saw in Turkey at people critical of Erdogan: they worry about more conservatism he might execute in the future. And while fearing the future, they overlook his successes today and the fact that none of the things they fear, have actually happened. A Turkish-German student stated it clearly to us: ‘I’m against him, because we fear that we can’t go out like this (without headscarf, short dress) anymore. He is conservative, so that might get the overhand one day.’

Another group is not per se pro Morsi, but pro Democracy. They say that the Egyptians should give Morsi time deliver his results, because he was democratically elected and this process, this agreement that Egyptians have made with each other, should be respected. They argue that when the president fails to deliver, the democratic system should be used to change this. Problem is, there are essentials missing in this system: there is no parliament, no adequate platform for debate, not yet a thorough understanding everywhere of what democracy is.

We must understand that the Egyptians may not be used to building their opinions and using debate as the Western world is. Mubarak ruled for 30 years, the army is powerful and acts independently, elections were installed quick & dirty. Do people understand that it means compromising, condemning violence and acceptance of the consequences of majority voices (or re-elect)?

We saw a piece on television on an German-Egyptian who in 2011 went into the country with a campaign bus, explaining to people in the country side with pictures and theater plays what democracy actually means. It reminded me a lot of human aid workers that explain the relation between condoms and HIV in small African villages who hear about safe sex for the first time.

Alaa, an English teacher we met from Alexandria, is supporter of this view. He asks himself the question ‘how democracy can function if the people elect somebody, and then change their minds after some time.’ He wasn’t happy about the military stepping in so soon, but knows that most people feel that the army acts in their best interest. As apposed to Ahmed, he wasn’t so convinced that the MB are terrorists. ‘Many friends of mine are MB, they strive for the same things as we do.’ Alaa had different things on his mind, though. Being a teacher, he depends on a stable and paying government and worried about job security. That’s why he accepted a job in Oman. Because of that and, saying it with a big smile, ‘because he also had some debts to pay off.’ Because I was laughing affectionately about his openness and the picture of him fleeing the country while being chased by angry men on these typical Egyptian flip-flops, I didn’t hear the ‘…debts that I want to pay off here.’ When we told him in return that we were on such a tight budget that we had such big breakfasts so that we could skip lunch and only pay for dinner, he had his share of laughter. We understood each other and had a jolly afternoon.

A third group is against turmoil and pro-economy. It’s likely we find these people working in tourism and depend mainly on confidence that Western tourists as well as investors have in Egypt. For example, tourism at the Red Sea has sunk to 15% of 2011 levels and in this region, where 40% of the families depend on good business. Sugran, an art student from Cairo we met today, said that the quietness around the pyramids was definitely a problem. But she ‘counted on the military to force a dialog between leaders or come up with a solution themselves.’

The fourth group is the army, a powerful, independently acting player. We don’t know much about their point of view. We met a Colonel in a men-café, but somehow we were a bit reluctant to ask him the same questions as the others. So that point of view is still to be discovered more.

So what do the Egyptians really want? Because from these dialogs, it is difficult to find the common grounds. Is it that they all want democracy? Seems not. It it the sentiment against the MB, or against terrorism, as the mass media connects these terms nowadays? But pro-what then?

So what do the Egyptians really want? Because from these dialogs, it is difficult to find the common grounds. Is it that they all want democracy? Seems not. It it the sentiment against the MB, or against terrorism, as the mass media connects these terms nowadays? But pro-what then?

Ahmed explained that many Egyptians return to their country to participate in the revolution, as some call it. They make a sign, holding 4 fingers up, the thumb folded. This is the sign pronounced as rabia, or four in Arabic. This word was in the name of the square on which the first large impeachment demonstrations were held (and the first people got killed). We saw some young people making the sign on the airport of Alexandria. It is not per se literally meant, but rather symbolic that you sympathize with the demonstrators. But on which side exactly, or on what the solution could be, the sign remains silent.

Ahmed explained that many Egyptians return to their country to participate in the revolution, as some call it. They make a sign, holding 4 fingers up, the thumb folded. This is the sign pronounced as rabia, or four in Arabic. This word was in the name of the square on which the first large impeachment demonstrations were held (and the first people got killed). We saw some young people making the sign on the airport of Alexandria. It is not per se literally meant, but rather symbolic that you sympathize with the demonstrators. But on which side exactly, or on what the solution could be, the sign remains silent.

Leave a Reply