A short history lesson on the Rwandan genocide

It made Cornelius feel proud of his country: at the border, German citizens can enter the country without visa. All others have to buy one. Why? We are guessing it’s because the Germans were the first colonialists from 1895 to 1916, before the Belgians took over after WWI. The Germans never really intervened with local politics or structures, something that the citizens came to appreciate a great deal after having experienced Belgian rule. Cornelius pushed the 30 USD for my visa through the window of the immigration officer and after smoothly finalizing customs procedures, we enter Rwanda.

Rwanda is a very small country, smaller than Baden-Württemberg with a population of 11 million people. It’s called the country of mille collines, or 1000 mountains, also the name of the famous hotel in which the events filmed in ‘Hotel Rwanda’ took place. There is hardly any flat spot, which forced the Rwandans to

P1060779create terraces for agriculture everywhere. With countless shades of green, the terraces make beautiful landscapes and the climate is nice and cool. The roads are of good quality and the streets are spic and span. It is hard to imagine that 20 years ago, one of the most horrible genocides the world has ever witnessed, took place here.

Originally, there was no one Rwandan peoples. There were 18 tribes consisting of Hutu and Tutsi. It was not ethnicity that distinguished people from each other, but tribe. The Twa, a tribe that also lives in Uganda, Congo and Burundi, made up a small minority. Before Belgian rule, the Rwandans were said to live peaceful together. For centuries, the country had a feudal structure in which the Tutsi had dominated the Hutu. The Tutsi were an aristocratic minority that ruled, owned politics, that owned cattle and land. The Hutu lived and worked agriculturally on Tutsi land, paying part of their crops as taxes. Division between people was socio-economic, not ethnic. Both accepted the situation and there had indeed been peace and stability, but some say that already before the Belgians started interfering, the Hutu grew more and more dissatisfied with their elite landlords and their own inferior position.

In the 30s, the Belgians aimed to tighten their grip on the country, to increase their power. And like most colonial rulers, they follow a divide-and-conquer strategy: they categorized people along ethnic lines by giving them the label Hutu or Tutsi, regardless of tribe. How they made this very random distinction: people that owned more than 10 cows were named Tutsi, people with less cows were Hutu. People were forced to carry an identity paper with a large H or T stamped on it. The Belgians had always supported the Tutsi, using them as political allies, favoring them with high positions and resources. This, combined with the ethnic segregation and the identity cards increased tension between the two parties. Additionally, the Belgians saw the growing anti-Tutsi sentiment by the larger Hutu group as an opportunity and changed allegiance: they dropped the Tutsi and made the Hutu their ally, which further incited hatred between the groups.

In the early 60s, tensions climaxed for the first time and the country counted 4 waves of tens of thousands Tutsi massacred by the Hutu.

The country gained independence in ’62, leaving rule to the moderate prime minister Kayibanda. For awhile, the future of Rwanda looked hopeful until in ’73 the radical and fascist Habyarimana seized power. He built a very effective army, the Interahamwe, and fed the Hutu his divisive ideology on a daily basis: these cockroaches (the Tutsi), should be eliminated. The country should be cleansed, and everybody, every Hutu, should pick up a weapon and start the process today. In the period between independence and 1990, 700.000 Tutsi fled the country and tens of thousands were killed.

In the meantime, Paul Kagame (the current president of Rwanda) had built his own opposition army in Uganda, working together with Museveni (the current president of Uganda) in ending the Idi Amin and Obote terror regimes there. He had trained and perfected his army and on 1 October 1990, his Rwanda Patriotic Front (RPF) marched up to Rwandas capital to overtrow the fascistic Hutu MRND party and conquer the Interahamwe army. This could have been effective, but France stepped in and provided the radical party with weapons, money and training to stop the RPF. Both Belgium and France kept on supporting the fascist regime and between 1990 and 1994, 8 smaller genocides took place.

Hutu president Habyarimana felt the pressure and softened his radical vision, he declared willingness to reunite the two groups and to share power. His fanatic rebels didn’t like this at all. When his plane was shot down, his own Interahamwe army were the alledged terrorists. And from that day, not even an hour after the plane crashed into the runway, the first roadblocks appeared. It was April 6, 1994, and the genocide started in full force.

In 100 days, the Hutu slaughtered 1 million Tutsi, moderate Hutu and Twa and hundreds of thousands in exile. I say here slaughtered, because that’s what is was: brutal killing. Tutsi were bludgeoned to death, burnt, buried alive, women raped and then killed, skulls split by machetes. There were stories of priests reporting hundreds of Tutsi hiding in their church, after which the church was set on fire, killing all refugees. Stories of women raped by HIV positive men but spared to die later of the disease. Stories of children having to kill their parents before being killed themselves.

The Hutu ignited a very effective propaganda machine: they used radio and village campaigns to motivate all Hutu citizens, to pick up a weapon, any weapon, and kill the Tutsi and moderate Hutu. This brainwash was very effective and almost all Hutu people old enough to play their morbid part, did so.

Before April, the highest UN commander in charge in Rwanda warned the UN headquarters that a genocide was coming, that he needed 5000 soldiers to prevent it. But he got a fax back from Kofi Annan that ‘they would not intervene before the Committee had formed an opinion’. Only when the genocide was at its end, the 5000 men landed in Uganda. Meanwhile, the international community watched and did nothing while 1 million people found death and 2 million turned into refugees.

What shocked us most, is not only the magnitude of the genocide, but foremost the role that normal, Hutu civilians played. Normal people, fathers, sons, truckdrivers, doctors, turned in or killed their neighbors, friends, employees, church members. And not only killed them, but butchered them in ways we couldn’t even imagine. In other genocides the evil was primarily done by the militia, rebels, armed professionals. Normal civilians may have played their part by looking away or not providing help, but here normal people turned into assassins. Why? What was the difference between this genocide and for example the holocaust in Germany or the erasing of the Armenians in the Ottoman empire? Were Rwandan people so different from the Germans or the Ottomans then? Was it the propaganda machine? Was it African tribal culture?

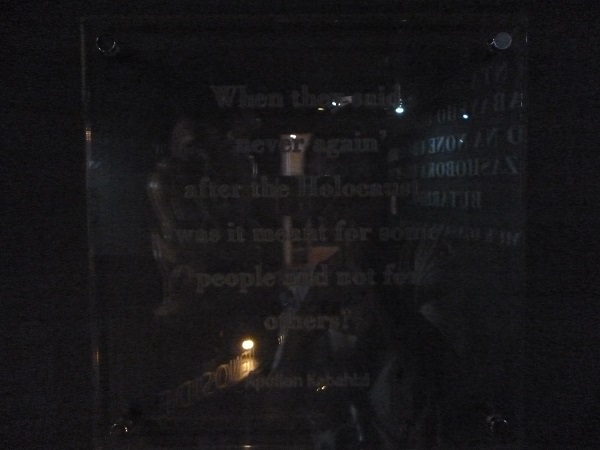

The Genocide Memorial Center also had a section on other genocides. ‘To put the Rwandan civil war in perspective’, they told us. What perspective? They showed explanations, pictures and personal stories of the genocides in Namibia, during WWII, in Armenia and in Bosnia. We were looking for lessons learned and essentials on how to prevent genocides. We scrutinized the text for similarities, differences and causes. We tried to find something on efforts done today to educate people, to see how it changed decision making at UN Headquarters. But we found nothing.

In fact, this addition without conclusions gave us a slight feeling that Rwanda tried to lift some heaviness from their history by showing that other countries did even worse. ‘See? There were 1,5 million Armenians killed. See? 6 million Jews.’ Maybe that’s what they meant by putting things in perspective.

The center was not so forgiving towards other countries. When Cornelius read sentences like ‘the German people killed…’ and ‘Germany still hasn’t compensated its warcrimes’, he felt a bit offended. The feeling of victory he had when entering the country vaporised then and there.

Today, Rwanda is all about forgetting the past and focus on a peaceful future of one Rwanda. This bears great similarity to the situation in South-Africa after Apartheid (I’m actually writing this on the day that Nelson Mandela passed away, a symbolic coincidence).

There are no Hutu and Tutsi anymore, there is only one peoples. It is said that 90% of all Hutu have blood on their hands, most of them are still alive and living safely and happily. In the aftermath of the civil war, around 100.000 people were brought to court, in my opinion a negligable figure when you compare that to the calculated 800.000 that committed war crimes. Intuitively, you think that the right thing to do is to have all criminals stand trial. On the other hand, how can you move forward as a country when almost half of your population would end up in jail? What would the economic impact be and what would it do to the national psyche?

I felt my eyes becoming wet when I read this quote from a girl that survived: ‘I’m apprehensive about the future, don’t know how I will survive. How can I live when my whole family is killed, I am all alone and I see the killers walking around every day, free, never having to face justice?’